A storm was brewing in Alabama—not one of weather, but of controversy. In a state with a historic reliance on prison labor, a van crash in 2024 highlighted ongoing issues, stirring public outcry. The accident, involving prisoners working for private companies, raised questions about safety, oversight, and the very ethics of the state’s convict work programs.

For over a century, Alabama has woven a complex narrative with prison labor at its center. Historically rooted in the post-Civil War era, the state became a pioneer of convict leasing, a system that replaced slavery with forced labor. Fast forward to today, and the 13th Amendment’s exception for incarcerated individuals continues to raise eyebrows. Despite Alabama formally ending convict leasing in 1928, the implications of its past linger on, influencing modern-day practices.

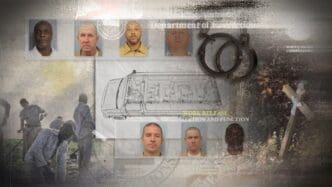

The tragedy of a transport van crash in April 2024, resulting in the deaths of Willie Crayton and Bruce Clements, draws attention to the perils encountered by prisoners in Alabama’s labor system. Jake Jones, a fellow inmate with a hasty driving reputation, was inexplicably assigned to drive under perilous conditions, despite a history of misconduct. This incident became infamous for exposing the legislature’s neglect and the lack of adequate supervision.

Alabama profits significantly from prison labor. Since 2000, it has amassed more than $250 million through deductions from prisoners’ wages. The incarcerated, a majority of whom are Black, are coerced into rigorous labor, from menial jobs within facilities to more demanding tasks outside prison walls. Often, these assignments come with steep deductions, including $5 daily charges for transport to work. While the labor may offer a semblance of freedom and income for prisoners, refusal invites punitive measures, like denied family visits or harsh reincarceration at high-security facilities.

Critics, like lawmaker Chris England, highlight the contradictions within the system. In a state with some of the lowest parole rates nationwide—just 8% in recent years—questions arise. How can prisoners be deemed dangerous for release if they often work unsupervised outside prisons? This paradox feeds into the narrative of a system prioritizing profits over rehabilitation.

As corporations like McDonald’s and Wendy’s face scrutiny, and lawsuits challenge the notion of forced labor, Alabama’s prison labor system finds itself at a crucial crossroads. Efforts calling for reform and ethical practices grow louder, demanding fair wages, safe conditions, and voluntary participation for the incarcerated workers. Meanwhile, stories like that of Arthur Ptomey, who was denied parole over a wage dispute, underscore the struggles faced by those entangled in this web.

Willie Crayton’s death added fuel to the fire, symbolized by a cross adorned with his hat. The crash that claimed his life revealed deeper issues within the state’s corrections department and the unsupervised freedom granted to inmate drivers like Jones. Public scrutiny intensified, as did calls for justice and accountability.

Amid evolving litigation and public sentiment, Alabama faces a moral question: Can it continue leveraging its incarcerated for profit, neglecting the human cost? The van crash may have served as a wake-up call, but the changes it inspires depend on the state’s willingness to reckon with its long-standing practices.

The story of Alabama’s practice of profiting from prison labor is a complicated one, rooted deep in historical practices yet relevant in today’s discussions of ethics and justice. The van accident serves as both a reminder and a call to action, illustrating the urgent need for reform in a state entrenched in its past. As Alabama navigates its future, the eyes of the nation remain fixed on its ability to transform an exploitative system into one that values human dignity over profit.

Source: Apnews