The face of the United States President, Donald Trump, appears on the flat-screen TV that Luis Olea purchased with money earned by transporting migrants through the remote Panamanian jungle during an unprecedented migration wave. The Darién Gap, a nearly impenetrable stretch of tropical rainforest along the Colombian border, turned into a migration highway in recent years, with over 1.2 million people from around the world traveling north toward the United States. This influx sparked an economic boom in areas hours or even days away from cities or mobile phone signals. Migrants paid for boat rides, clothing, food, and water following exhausting and often deadly treks.

With this surge of wealth, many in villages like Villa Caleta, where Olea resides in the indigenous Comarca lands, abandoned their banana and rice crops to transport migrants along winding rivers. Olea installed electricity in his one-room wooden home deep in the jungle. Families invested in their children’s education, and people built homes and hopeful futures. However, the money disappeared when Trump returned to the White House in January and restricted asylum access in the U.S., causing migration through the Darién Gap to plummet. The new economy collapsed, leaving residents scrambling for alternatives. Olea remarked that they once relied on migration, and now they are left with nothing.

Migration through the Darién Gap surged around 2021, as people fleeing economic crises, wars, and repressive governments increasingly dared to undertake the multi-day journey. While criminal groups profited by controlling migration routes and extorting vulnerable individuals, the massive movement also injected money into historically underdeveloped regions. It became a business opportunity for many, akin to discovering a gold mine, but once depleted, people either moved to cities or remained in poverty.

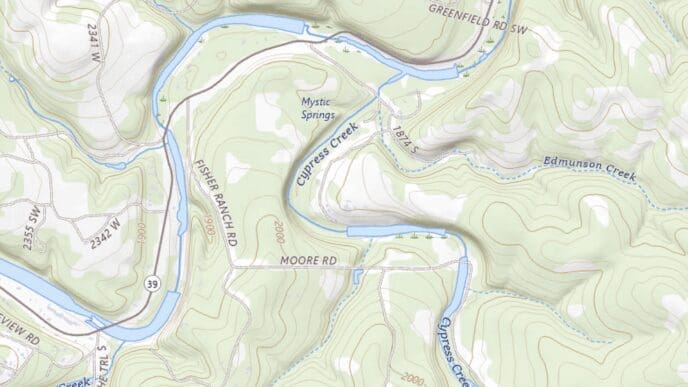

Olea, like many others in the Comarca, survived by cultivating bananas in the jungle near Villa Caleta, close to the Turquesa River flowing near the Colombian border. However, when migrants started moving through the region, he and others invested in boats to pick up people in the village of Bajo Chiquito, where migrants arrived after their brutal journey. The boat operators, known as “lancheros,” transported migrants to a port, Lajas Blancas, from where they took buses northward.

Some, like Olea, made up to $300 a day, far exceeding the $150 monthly income from farming. The activity became so lucrative that villages along the river agreed to take turns transporting migrants, ensuring that each community got its share. Olea installed solar panels on his tin roof, elevated his home to protect belongings from floods, and purchased a water pump and a television. Now, he watches Trump discuss tariffs on CNN en Español. The money connected him and the Darién communities to the world in a way that never existed before.

However, with migration dwindling, many residents were left stunned by the abrupt economic downturn. The community leader, Cholino de Gracia, noted that the lack of resources is affecting food availability, as there are no supermarkets nearby. Olea has resumed banana cultivation, but it will take at least nine months to yield produce. Although he could sell his now-unused boat, he questioned who would buy it, as there’s no market anymore.

Pedro Chami, another former boat operator, has turned to carving wooden trays outside his home and hopes to try his luck searching for gold in the river sand. At the height of the migration wave, Panamanian authorities estimated that 2,500 to 3,000 people crossed the Darién Gap daily. Now, the figure is around ten per week.

Many more migrants, primarily Venezuelans, have begun heading south along Panama’s Caribbean coast in a reverse flow back home. The Clan del Golfo, a criminal group that profited from northward migration, is now exploring the coast for opportunities with those traveling in the opposite direction.

Lajas Blancas, once bustling with people buying food, SIM cards, blankets, and phone charger access, has transformed into a ghost town with signs advertising “American clothes” in red, white, and blue. Zobeida Concepción’s family is among the few who haven’t left Lajas Blancas. She noted that most vendors who sold goods to migrants have relocated to Panama City for work. The family sold water, soft drinks, and snacks and even temporarily opened a restaurant, buying new beds, a washing machine, a refrigerator, and freezers to store products sold to migrants. They even began constructing a house.

Concepción is unsure of the future but has some savings and plans to keep her freezers for potential future opportunities when another government enters the White House, pondering what the future might hold.

Your World Now

The migration route through the Darién Gap, once a thriving source of income for local communities, has experienced a dramatic shift following changes in U.S. asylum policies. This shift highlights the dependency that many regions can develop on migration, which can lead to sudden economic disruptions when policies change. Residents who previously benefited from the influx of migrants now face financial uncertainty and must explore alternative means of livelihood.

The broader implications of such shifts can affect not only local economies but also influence migration patterns, regional stability, and the socio-economic dynamics of areas along migration routes. Communities that once thrived on income from migrant services must adapt to new realities, which may involve returning to traditional agricultural practices or seeking other forms of employment. This situation underscores the importance of diversifying economic activities to build resilience against policy changes that can dramatically alter local economies.