In a severe crackdown on dissent, the Nicaraguan government, led by President Daniel Ortega, has rendered hundreds of its citizens stateless, scattering them across the globe.

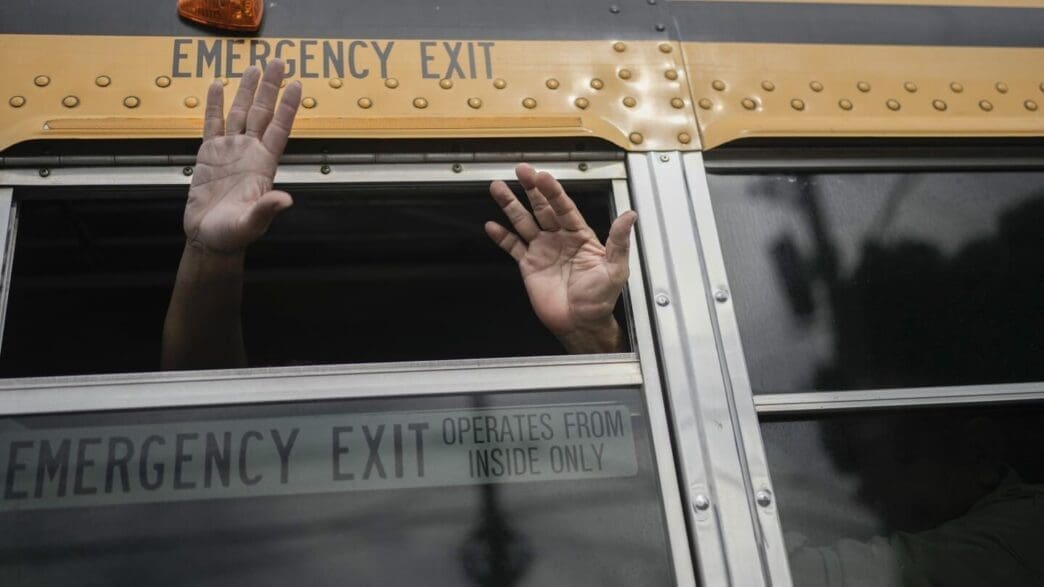

In a shocking move, President Daniel Ortega’s government transported Sergio Mena and 134 other prisoners from Nicaragua to Guatemala. This group joined 317 others who had been stripped of their Nicaraguan identities, labelled as adversaries by the government. Among those affected are religious leaders, students, activists, dissidents, and journalists, who now find themselves living in a precarious limbo, detached from their legal rights and identities.

Sergio Mena, a rural activist, fled Nicaragua in 2018 amidst a government crackdown against dissenters, only to be imprisoned upon his return in 2021. Mena describes the harrowing experience of torture during his imprisonment, where he and others were subjected to both physical and psychological abuse. Released yet stateless, Mena remains in exile in Guatemala, grappling with the challenges of life without citizenship. “We were tortured all the time, physically and psychologically,” he recalls. The absence of citizenship denies people like Mena access to basic services and rights, leaving them in a state of perpetual uncertainty and fear.

Karina Ambartsoumian-Clough, executive director of the U.S.-based organization United Stateless, highlights the profound impact of statelessness, stating it as a form of torture. Without valid identification documents, stateless individuals face significant barriers in accessing employment, education, healthcare, and even basic financial services. The United Nations estimates that 4.4 million people worldwide are stateless, underscoring the gravity of this global issue.

The Ortega administration has not provided a clear rationale for stripping citizens of their nationality nor for Mena’s release. However, international observers suggest that the move may have been an attempt to mitigate criticism while maintaining an iron grip on perceived enemies. This tactic has left many exiles, including Sergio Mena, anxious about the reach of the Nicaraguan government even in their current places of refuge.

Allan Bermudez, once a university professor, faced accusations of conspiracy against Ortega’s government and was forcibly sent to the United States with 222 other prisoners. Despite receiving temporary support from the U.S. government, Bermudez’s life is now dominated by instability. Working at a fast-food chain, he contends with health issues and financial difficulties, struggling to secure asylum and rebuild his life away from Nicaragua.

Amidst these struggles, the exiled Nicaraguans face additional challenges posed by shifting political landscapes. The Biden administration offered temporary protections, but these may dissipate under future U.S. leadership. Meanwhile, Spain has proposed granting nationality to some stateless exiles, yet the process remains fraught with complexities and resource constraints.

Many of those exiled hold onto hope of returning to Nicaragua, yet for others, like 82-year-old Moises Hassan, that hope has waned. Once a prominent figure who fought alongside Ortega, Hassan now remains hidden in Costa Rica, too fearful to venture into areas where he might be recognized by Ortega’s agents. The stripping of his citizenship and pension has left him dependent on his family, underscoring the deep personal and economic toll of such political actions.

The plight of these Nicaraguan exiles highlights the severe impact of losing one’s nationality, as they navigate life in foreign lands under constant threat and uncertainty. Their stories underscore the urgent need for international attention and support to address the challenges faced by stateless individuals worldwide.

Source: APNews